|

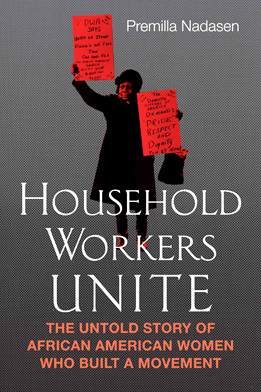

Household

Workers Unite

by Premilla Nadasen

c.2015, Beacon Press

$27.95 / $33.00 Canada

248 pages

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

The Truth Contributor

There is not a speck of dust in your home.

The floors gleam, the kitchen shines, the bathroom sparkles,

and rugs are fluffy again. You’ve changed bedsheets and you

even washed windows. You’re ready for fall and thankful for

the help you had getting this way; if that help was paid,

read Household Workers Unite by Premilla Nadasen,

and you’ll be thankful for even more.

|

|

|

Picture this: a white reporter encourages African-American

maids to “speak out about their hardship” and the women who

employ them. You know the movie, but did you recognize the

“victimization theme?” Yes, says Nadasen, The Help

“reinforces dominant stereotypes of passive household

workers,” even though there was historically nothing passive

about them…

In the years following the Civil War, the “Mammy” figure

took hold in white America, becoming somewhat of a cult

based on the idea of a loyal, maternal female slave. That

vestige of slavery (and inherent racism) generally affected

how African-American domestic workers were treated by white

female employers then, but “new ideas were germinating.”

In 1881, black laundresses formed a “Washing Society” and

eventually went on strike for higher wages. Activism never

stopped, but there was a setback in the fledgling movement

during the Depression, when black domestics found day-work

by sitting in a street corner “slave market,” and that

didn’t go unnoticed. By 1934, journalists, activists, and

other black feminists threw their support behind Dora Jones,

who led the Domestic Workers Union (founded in 1934) in New

York.

Nurse, midwife, and housekeeper Georgia Gilmore used her

cooking skills to raise money for “The Club from Nowhere,” a

group supporting activists and organizers both financially

and with food. Undoubtedly, the Civil Rights Movement

spurred Atlanta’s Dorothy Bolden to work with Dr. King on

behalf of household workers. Cleveland’s Geraldine Roberts

founded the Domestic Workers of America. Edith Barksdale

Sloan pushed the movement along when she became head of the

National Committee on Household Employment. Other

influential women bore their share of the movement, just as

today’s activists help protect the workplace rights of

caregivers, personal helpers, and domestic workers of all

races.

Imagine seeing a federally-funded monument to the “black

mammy,” standing in our nation’s capital. Yep, in 1924, the

United Daughters of the Confederacy tried to build exactly

that, and it was “furiously opposed.”

That’s just one of the stories you’ll read inside

Household Workers Unite.

Stories, says author Premilla Nadasen, are what she tried to

fill her book with, in fact, and she somewhat succeeds.

There are, indeed, a lot of stories here, but there’s plenty

of dryness, too, in the form of names, dates, and acronyms

that ultimately become quite overwhelming. My advice is to

try and get through them; this book is powerful and

inspiring, but the voices and their memories are what

matters.

This isn’t your curl-up-in-front-of-a-fireplace kind of read

but it is a pleasure, especially if you’re a historian,

feminist, or domestic worker yourself. Household Workers

Unite will make you think as it eats up every speck of

your time.

|